Some writers never struggle to find enough words; they struggle to prune over-long manuscripts. Other writers, like me, start out with a premise and work through an outline to a rough draft that is . . . short.

As I expand on my first draft, I worry about length. Optimal length for a novel (most genres) is between 70,000 and 90,000 words. What if your story comfortably winds up in the low range, 30-000-50,000?

You have a choice: complicate and expand to novel length or call it a novella.

In an article for Writer’s Digest, Chuck Sambuccino addresses this choice. His advice: Expand your story until it’s a novel. But he is talking to writers who want to query agents and land contracts with major publishers. Print publishers will rarely take on a novella, and “rarely” probably means “never” for the unknown first-timer.

The novella has taken on new life in recent years, however, with the rise of digital publishing. Remove the cost of hard copy printing, binding and distribution, and the shorter literary forms are more than viable—they are attractive to readers and authors alike.

The novella has taken on new life in recent years, however, with the rise of digital publishing. Remove the cost of hard copy printing, binding and distribution, and the shorter literary forms are more than viable—they are attractive to readers and authors alike.

The novella is a time-honored and well established literary tradition—I need only mention Joseph Conrad, Edith Wharton and Ernest Hemmingway. An interesting article on the novella in Wikipedia includes a reading list that will keep you happy for a couple of months at least.

What the novella can do for you

Everybody knows that after the blog tour and the boosted posts, the best way to keep your book selling is to write more books. With a very small publisher, or by self-publishing, you can get new titles out there about as fast as you can write them. But if you once make the leap to the big-time, the process slows down. How do you stay on the radar in this fast-paced market?

Thought I Knew You is currently #11 in the Paid Kindle store on sale for $.99 (as of today, August 17, but not for long)

One way is to write a novella. Case in point:

Bestselling author Kate Moretti debuted her knockout first book, Thought I Knew You (Red Adept Publishing), in September 2012. She followed with Binds That Tie a year and a half later, in March, 2014. About that time, TIKY hit the New York Times bestseller list, and Moretti caught the eye of literary agent Mark Gottlieb at Trident Media Group. Gottlieb parlayed this fast start into a two-book deal with Atria (Simon and Shuster).

Moretti had momentum and a growing fan base. But by stepping up to the big five, she was facing a two-year gap between book two and book three. How to keep her fans engaged? Enter the novella.

At half the length of a full novel (and proportionately fewer subplots and complications), the novella can be written in half the time. A small independent publisher can turn the ebook around in half the time it takes a major print publisher to get a novel out the door.

While You were Gone is a tangent to TIKY, with all new characters, as engaging as we have come to expect from Moretti, plus a tight, fast-paced story, and a strong twist at the end. It is available for pre-order now, at $2.99, and will be released on September 1, 2015.

While You were Gone is a tangent to TIKY, with all new characters, as engaging as we have come to expect from Moretti, plus a tight, fast-paced story, and a strong twist at the end. It is available for pre-order now, at $2.99, and will be released on September 1, 2015.

From a fan’s perspective, this is perfect—a short (130 pages) dose of Moretti’s unique blend of mystery/suspense and women’s fiction between the longer works. From the author’s perspective, she stays out front on the market with a book and keeps building her fan base in preparation for The Vanishing Year (coming in 2016). This is what a novella can do for you.

Kimberly Giarratano has done the same thing. Readers loved her YA mystery with ghosts, Grunge Gods and Graveyards (4.7 out of 5 stars on Amazon, based on 74 reviews). That book came out in May 2014, and Giarratano followed up just one year later with a spin-off novella, The Lady in Blue, which she self-published.

Giarratano takes the logic one step further. In between GGG and LIB, she self-published a lovely YA ghost story, One Night is All You Need—just 21 pages, but hey, it’s free! And a reader who gets a taste of this story and likes it (how could you not) will surely take a look at one of the other books.

All this is good news to me. When I start working on a story and doubt assails me as to whether I have material for a 90,000-word novel, I relax. If it comes out short, I will have written a novella.

I love reading them myself. More than a short story, less than a novel, just the right length for a late-summer afternoon curled up in the reading chair. Perfect!

Elizabeth Buhmann is the author of Lay Death at Her Door: “The bill for lies told decades earlier comes due for Kate Cranbrook, the complex narrator of Buhmann’s superior debut… and more blood is shed along the way to a jaw-dropping, but logical, climax that will make veteran mystery readers eager for more.” Publishers Weekly (starred review)

Elizabeth Buhmann is the author of Lay Death at Her Door: “The bill for lies told decades earlier comes due for Kate Cranbrook, the complex narrator of Buhmann’s superior debut… and more blood is shed along the way to a jaw-dropping, but logical, climax that will make veteran mystery readers eager for more.” Publishers Weekly (starred review)

![img_2570[1]](https://austinmysterywriters.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/img_25701.jpg?w=150&h=113)

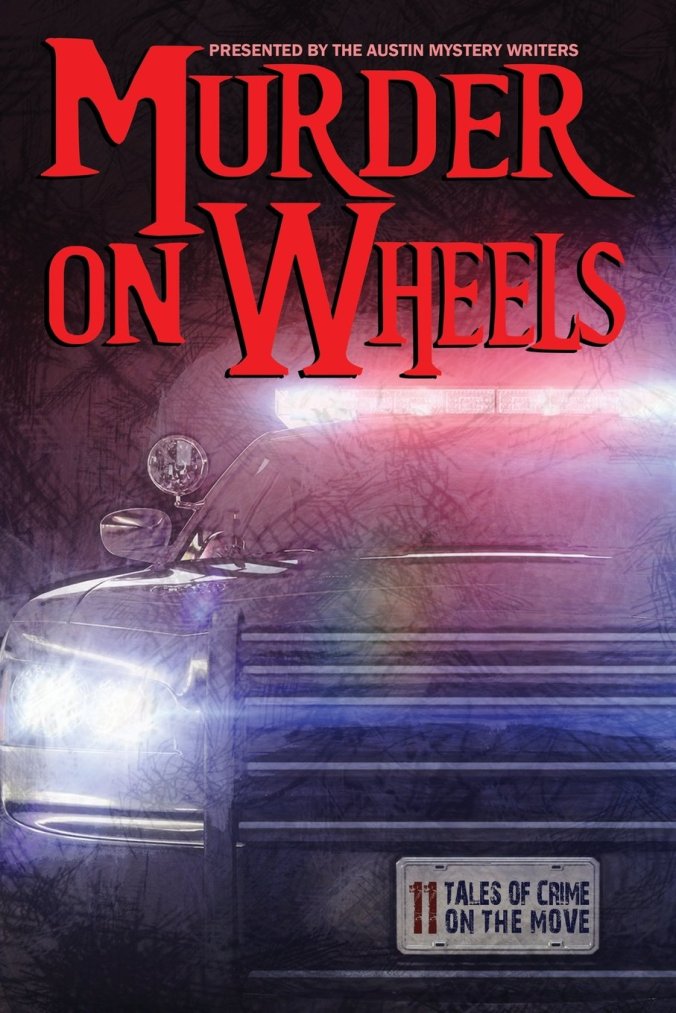

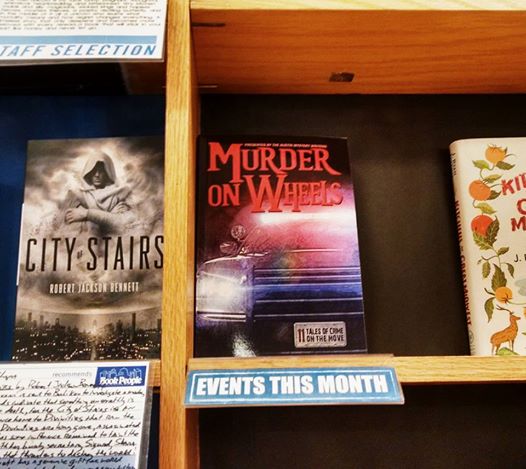

Who are these folks? (clockwise) Kaye George, Laura Oles, Scott Montgomery, Kathy Waller, Gale Albright, Valerie Chandler, Reavis Wortham, Kaye George, Earl Staggs–the eight writers who made Murder on Wheels what it is. And Kaye George is in there twice because it was her idea in the first place.

Who are these folks? (clockwise) Kaye George, Laura Oles, Scott Montgomery, Kathy Waller, Gale Albright, Valerie Chandler, Reavis Wortham, Kaye George, Earl Staggs–the eight writers who made Murder on Wheels what it is. And Kaye George is in there twice because it was her idea in the first place.