by Helen Currie Foster

November 24, 2025

Writers live in trepidation that they’re failing a much-publicized writing test: a great first line.

Maybe that’s not a fair burden. If I already like a writer’s work—a favorite mystery-writer, for instance–I don’t demand a blockbuster first line. But I do need reassurance that I’m going to like that writer’s new book as well as the last. So on the opening page, I hope to see a reminder of the detective’s personality, of an interesting setting, of the vagaries of the detective’s colleagues.

If, however, it’s my first encounter with an author—I need to be drawn in swiftly. Looking at first lines (and what immediately follows) is a good exercise. Each reader knows when the opening has worked, and they’re hooked on a story—or not. Maybe the lesson is this: when the reader’s eyes fall on the first page, the writer must promise the story!

“Tell me a story!” That’s what we’re looking for when we open a book. The first sentence, the first page, needn’t summarize the book, but we want very quickly to know we’re going to get a story.

Here’s a first line that kept me reading: “When Augustus came out on the porch the blue pigs were eating a rattlesnake—not a very big one.”

Blue pigs? I’d never heard of blue pigs, much less pigs dining on rattlesnake. Of course I kept reading, just to hear more about Augustus: “Pigs on the porch just made things hotter, and things were already hot enough. He stepped down into the dusty yard and walked around to the springhouse to get his jug.” By then the reader might also be feeling thirsty and might wonder if Augustus would share that jug… but the author hadn’t finished:

“[T]he sun had the town trapped deep in dust, far out in the chaparral flats, a heaven for snakes and horned toads, roadrunners and stinging lizards, but a hell for pigs and Tennesseans.”

What a setting, and what a contrast to Augustus’s home—he’s stuck in godforsaken dusty chaparral flats, heaven for snakes and horned toads, and far from the moist green hills of Tennessee.

McMurtry’s first sentence is great. But then he gives us just a couple more sentences—and we find ourselves already longing to hear more about Augustus as the saga begins—Lonesome Dove, of course, and thank you, Larry McMurtry.

The on-line lists of “famous first lines” include perennial favorites. Of course Moby Dick is famous—“Call me Ishmael.” We’re notified that our protagonist will be wandering far….

Also there’s Pride and Prejudice: “It is a truth universally acknowledged that a single man in possession of a good fortune must be in want of a wife.” Jane Austen doesn’t keep us waiting. By the end of the first page we know that “a single man of large fortune” has arrived in the neighborhood—and we tingle in anticipation of the plot suggested in the opening sentence.

What about Shogun? The first line of James Clavell’s novel hauls us in: “The gale tore at him and he felt its bite deep within and he knew that if they did not make landfall in three days they would all be dead.” Then, “Too many deaths on this voyage, he thought, I’m Pilot-Major of a dead fleet. One ship left out of five—eight and twenty men from a crew of one hundred and seven and now only ten can walk and the rest near death and our Captain-General one of them. No food, almost no water and what there is, brackish and foul.”

What will happen? Will the pilot survive? We’re hooked by the first sentence, and the next few sentences convince us that we’ve got a tale to read in Shogun. Even if we’ve never yet read any Clavell, we’re confident—as we are in Lonesome Dove, and in Pride and Prejudice––that the author’s got a story for us.

Hilary Mantel is a genius at first lines. The Mirror & the Light begins In London, in May 1536, with this sentence: “Once the queen’s head is severed, he walks away.” It takes another page before we begin to grasp that “he” is Cromwell, attending the execution of Anne Boleyn. And already we know that this story will be frightening.

As a lover of mystery novels, I’m critical about beginnings. I liked Batya Gur’s mysteries, set in Jerusalem, with Chief Superintendent Michael Ohayon. Here’s the first line of Bethlehem Road Murder:

“There comes a moment in a person’s life when he fully realizes that if he does not throw himself into action, if he does not stop being afraid to gamble, and if he does not follow the urgings of his heart that have been silent for many a year—he will never do it.”

Okay, but who’s thinking that? The next sentence reveals the thought belongs to Chief Superintendent Ohayon himself, and he’s thinking that thought while he’s engaged in leaning over a woman’s corpse and trying to get a better look at the silk fibers from the rip in the scarf around her neck. In other words, our detective’s already on the job—but what are the “urgings of his heart” that we just heard about? I’m hooked—we have a corpse, a murder (surely a mystery to solve)—and also a mystery about what’s bugging our protagonist.

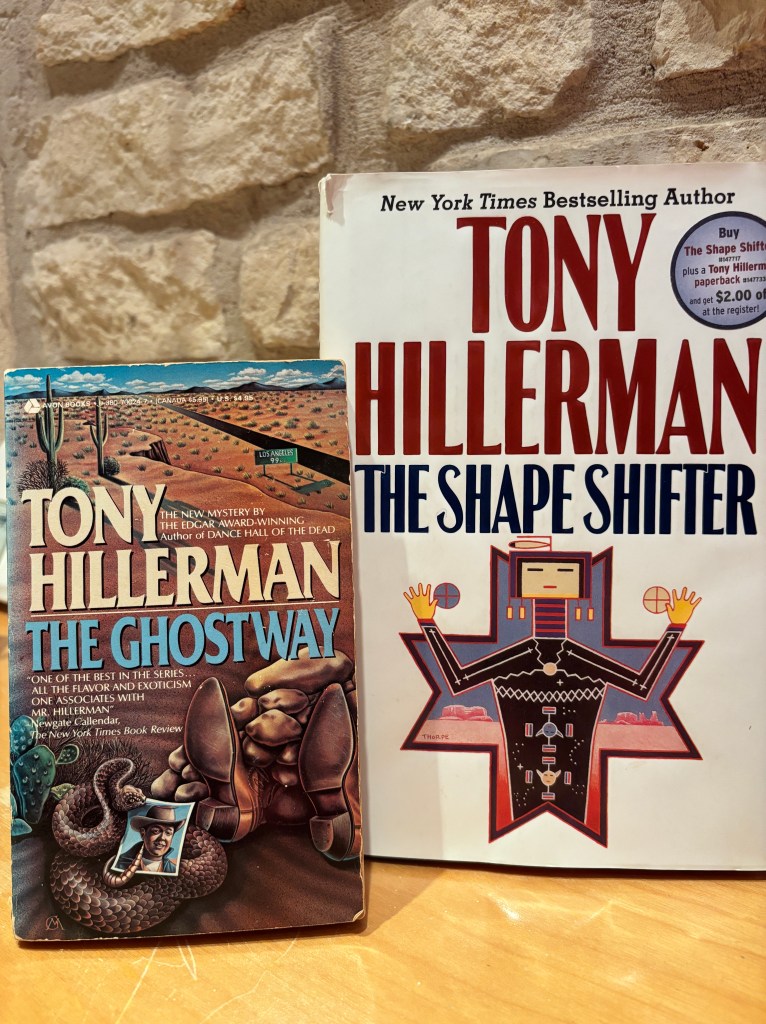

Here are the first and second line of one of Tony Hillerman’s later mysteries, The Shape Shifter (2006):

“Lieutenant Joe Leaphorn, retired, stopped his pickup about a hundred yards short of where he had intended to park, turned off the ignition, stared at Sergeant Jim Chee’s trailer home, and reconsidered his tactics. The problem was making sure he knew what he could tell them, and what he shouldn’t, and how to handle it without offending either Bernie or Jim.”

If you didn’t already know Lieutenant Leaphorn, you’d at least grasp from the first sentence that he’s tactful, careful, thoughtful. But what’s the issue he’s wrestling with? We’ll know by the end of the paragraph, and we’ll be deep into a new story. Just as we hoped.

And here’s the first line of Hillerman’s earlier The Ghostway (1986): “Hosteen Joseph Joe remembered it like this.” The next paragraph explains how this witness “noticed the green car just as he came out of the Shiprock Economy Wash-O-Mat…The car looked brand new and it was rolling slowly across the gravel, the driver leaning out the window just a little.” And what Hosteen Joseph Joe remembered next was that the driver—though he looked like a Navajo—had yelled at Joseph Joe, who was eighty-one, and “that was not a Navajo thing to do.” We already feel a story—why would someone yell at Hosteen Joseph Joe?—but by the time Hosteen Joseph Joe winds up his narrative (just paragraphs later) he has also described the ensuing pistol shot leaving a dead man on the ground. Who was murdered? By whom? Why? We’ve definitely got a story.

If you read Reginald Hill (his protagonists are Detective Superintendent Andy Dalziel and Peter Pascoe of the Yorkshire CID), you know that he begins every mystery differently. His Bones and Silence (1990) is no candidate for a mere “first sentence.” Instead, it opens with a letter to Superintendent Dalziel from an anonymous correspondent who intends to commit suicide, but wants to be in correspondence with Dalziel before this occurs. The letters continue to arrive for Dalziel for months—anonymous, and we don’t know whether the writer is man or woman—as he and Pascoe toil through a series of apparently unrelated murder investigations. We readers are kept in suspense until the very last page.

Finally—and do you remember being assigned this book?—consider this first sentence: “The cold passed reluctantly from the earth, and the retiring fogs revealed an army stretched out on the hills, resting.” Thus opens The Red Badge of Courage, by Stephen Crane. We see the landscape—and we see the army, “resting.” “Resting”? The army must need rest and we wonder why. “Resting” somehow builds suspense for what may follow –for what may happen when the army finishes resting. We know there’s a story––but we don’t know what, and we won’t meet that young private for a couple of pages more.

Our craving for stories is what makes us human. Think of the power of those four little words: “Once upon a time…!” Four words that assure us of a story. We gather around to hear it, whether we’re three, thirty, ninety.

Robert Louis Stevenson, author of such tales as Treasure Island and Kidnapped, was given a name by the Samoans: TUSITALA—the Teller of Tales. What an honor!

And that’s who we aspire to be. Raconteurs! Storytellers! Writers! Authors! Tellers of Tales!

And now–here in the Hill Country west of Austin, we finally (FINALLY) got some rain. Wishing you a HAPPY THANKSGIVING!

My latest tale, Ghost Justice, came out August 29, 2025. It’s Book 10 in the series involving Alice, a lawyer working in the small town of Coffee Creek in the iconic Texas Hill Country. Legal drama, and matters of the heart! The next tale is simmering! Find Ghost Justice at BookPeople in Austin or on Amazon. https://www.amazon.com/Ghost-Justice-Helen-Currie-Foster/dp/1732722943

Follow me at http://www.helencurriefoster.com.

In Chapter 1, Dr. Blair Cassidy, professor of English, arrives home one dark and stormy night, walks onto her front porch, and trips over the body of her boss, Dr. Justin Capaldi. She locks herself in her car and calls the sheriff. The sheriff arrives and . . .

In Chapter 1, Dr. Blair Cassidy, professor of English, arrives home one dark and stormy night, walks onto her front porch, and trips over the body of her boss, Dr. Justin Capaldi. She locks herself in her car and calls the sheriff. The sheriff arrives and . . . poisons. As a pharmacy technician during World War I, she did most of her research on the job before she became a novelist. Later she dispatched victims with arsenic, strychnine, cyanide, digitalis, belladonna, morphine, phosphorus, veronal (sleeping pills), hemlock, and ricin (never before used in a murder mystery). In The Pale Horse, she used the less commonly known

poisons. As a pharmacy technician during World War I, she did most of her research on the job before she became a novelist. Later she dispatched victims with arsenic, strychnine, cyanide, digitalis, belladonna, morphine, phosphorus, veronal (sleeping pills), hemlock, and ricin (never before used in a murder mystery). In The Pale Horse, she used the less commonly known  Aforethought.

Aforethought. for accuracy. Colleague

for accuracy. Colleague  writing. But she confessed in a magazine article that

writing. But she confessed in a magazine article that