by Dixie Evatt

O villain, villain, smiling damned villain. . .

That one may smile, and smile and be a villain. — William Shakespeare

Lately I’ve felt as if I have a sesame seed stuck between my molars. Except instead of an annoying seed, it’s an idea I can’t let go of. It started when a group of fellow writers were talking about overuse of certain pat descriptors to express emotions. “Smiled” is a common culprit. Now I’m haunted when I read my copy. Why are my characters always smiling? What kind of smile is it? Nervous smile, a smile to mask confusion, fake smile, cold-as-ice smile, snide smile, crooked smile, challenging smile, weak smile, infectious smile or just a plain old vanilla grin?

I can’t unsee the way I fall back on dull and overused expressions such as “she smiled,” instead of taking the time to ask myself, what underlying emotion is the character feeling? How can I describe that emotion so the reader understands it in a precise and fresh way? How can I eliminate all that superfluous smiling that goes on in my copy and instead home in on the intended emotion? In other words, when my characters smile, what emotion am I trying to communicate? Unless writing a picture book an author has only words to create an image in the reader’s mind.

My new-found fixation on smiling is now creeping into not only my writing but also into books I’m reading. Sometimes a smile is understood without the word being used as in The Frozen River by Ariel Lawhon. “Good humor stretches out from the corners of Ephraim’s eyes in the form of crow’s feet, and I realize he has lightened my mood on purpose.” Sometimes the smile is expressed unambiguously as in My Brilliant Friend by Elena Ferrante. “She made a half smile of contempt that meant: Marcello Solara makes me sick.” Or this from Vera Wong’s Unsolicited Advice for Murderers by Jesse Q. Sutanto. “They are sort of smiling, but the smiles are heavy and apologetic. . .these aren’t the kind of smiles you give when you have good news to share. They’re the kinds of smiles that know they’re about to ruin someone’s life.”

The scholar Paul Ekman has identified 18 common types of smiles with disparate meanings: the fixed polite smile (I really don’t know what to say); the embarrassed smile (I don’t know anyone); the tight-lipped relieved smile (oops, that was a close call); the exhausted smile (happiness after a long race); the sadistic smile (it particularly exudes evil); the exasperated smile (annoyance); the compliant smile (it will be over soon); the diplomatic smile (a “professional” smile); the ecstatic smile (life is wonderful); the exaggerated smile (imitation of joy, a little forced); the worried smile (the situation is really awkward); the contemptuous smile (one is secretly a bit spiteful); the ironic smile (welcome to sarcasm); the fake smile (to hide an emotion of weakness); the delighted smile (in front of a baby); the warm smile (that of a mother encouraging her child); the meditative smile (Buddha-like, filled with compassion); and the amorous smile (I adore you).

The scholar Paul Ekman has identified 18 common types of smiles with disparate meanings: the fixed polite smile (I really don’t know what to say); the embarrassed smile (I don’t know anyone); the tight-lipped relieved smile (oops, that was a close call); the exhausted smile (happiness after a long race); the sadistic smile (it particularly exudes evil); the exasperated smile (annoyance); the compliant smile (it will be over soon); the diplomatic smile (a “professional” smile); the ecstatic smile (life is wonderful); the exaggerated smile (imitation of joy, a little forced); the worried smile (the situation is really awkward); the contemptuous smile (one is secretly a bit spiteful); the ironic smile (welcome to sarcasm); the fake smile (to hide an emotion of weakness); the delighted smile (in front of a baby); the warm smile (that of a mother encouraging her child); the meditative smile (Buddha-like, filled with compassion); and the amorous smile (I adore you).

Ekman’s work was the basis of the American crime drama Lie to Me, in which an expert in facial expressions, tone of voice and body language uses his skills to help law enforcement uncover the truth.

We have Charles Darwin in his 1872 book (Expressions of the Emotions: Man and Animals) to thank for one of the earliest scientific studies of human emotions. What is important for writers is that he also offered analysis of the body language — facial movements, gestures, sounds, and the physiological changes — that go with different emotions.

William Shakespeare wrote more than two hundred years earlier than Darwin, about the trap of the hidden meanings behind a smile. For instance, Hamlet confronts the lie hidden in a devious smile when he realizes his stepfather, King Claudius, murdered his father, saying “O villain, villain, smiling damned villain. . .That one may smile, and smile and be a villain.” The notion of a misleading smile is something Shakespeare first visited in Act 4 of Julius Caesar, when Octavius says, “And some that smile have in their hearts, I fear. . . millions of mischiefs.”

Fortunately there are any number of guidebooks to help writers navigate this tricky smile business. Among them are S.A. Soule’s The Writer’s Guide to Character Expressions and Emotions; Valerie Howard’s Character Reactions from Head to Toe; Kathy Steinemann’s The Writer’s Lexicon: Body Parts, Action and Expressions; and The Emotion Thesaurus by Becca Puglisi and Angela Ackerman. Jordan McCollum’s three-part posting on the subject of avoiding overused “gesture crutches” is also helpful.

Fortunately there are any number of guidebooks to help writers navigate this tricky smile business. Among them are S.A. Soule’s The Writer’s Guide to Character Expressions and Emotions; Valerie Howard’s Character Reactions from Head to Toe; Kathy Steinemann’s The Writer’s Lexicon: Body Parts, Action and Expressions; and The Emotion Thesaurus by Becca Puglisi and Angela Ackerman. Jordan McCollum’s three-part posting on the subject of avoiding overused “gesture crutches” is also helpful.

These sources may also help writers avoid a second trap: overdoing tired descriptors to convey emotions. The conversation with other writers that set in motion my fixation on smiles was triggered by an article in which Mark Twain praised his friend, William Dean Howells. Twain minced no words about what he saw as overuse of empty stage directions to convey meaning while praising Howells as a master in the use of body language to describe thoughts and emotions without the need to be repetitive. “Some authors overdo the stage directions, they elaborate them quite beyond necessity; they spend so much time and take up so much room in telling us how a person said a thing and how he looked and acted when he said it that we get tired and vexed and wish he hadn’t said it at all,” Twain observed. He said directions such as “laughed” are worked to the bone when the author has given the character nothing to laugh about.

The lesson? Be clear about what kind of smile you intend but also give the character something to smile about.

***

A former political reporter in Austin, Dixie also taught writing at Syracuse University. When she teamed up with Sue Cleveland to write fiction, they sold a screenplay to a Hollywood producer. Although the movie was never made, the seed money financed ThirtyNineStars, their publishing company. Through it they published two award-winning thrillers (Shrouded and Digging up the Dead) under the pen name, Meredith Lee. Dixie’s first solo mystery was Bloodlines & Fencelines, set in a tiny Texas town near Austin. Kirkus reviews described the book as, “A twisty whodunit that’s crafted with care and saturated with down-home Southern charm.” She is working on second mystery in the series. www.dlsevatt.com

A former political reporter in Austin, Dixie also taught writing at Syracuse University. When she teamed up with Sue Cleveland to write fiction, they sold a screenplay to a Hollywood producer. Although the movie was never made, the seed money financed ThirtyNineStars, their publishing company. Through it they published two award-winning thrillers (Shrouded and Digging up the Dead) under the pen name, Meredith Lee. Dixie’s first solo mystery was Bloodlines & Fencelines, set in a tiny Texas town near Austin. Kirkus reviews described the book as, “A twisty whodunit that’s crafted with care and saturated with down-home Southern charm.” She is working on second mystery in the series. www.dlsevatt.com

***

Image of cookies by Steve Buissinne from Pixabay

Image of Tim Roth at the 2015 San Diego Comic Con International in San Diego, California. The Hateful Eight panel by Gage Skidmore, CC BY-SA 3.0 , via Wikimedia Commons

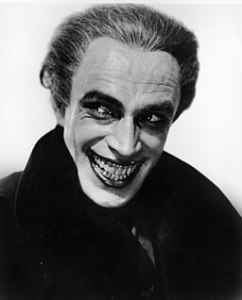

Image of actor Conrad Veidt in character as Gwynplaine from the American film The Man Who Laughs (1928). Universal Pictures, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Image of book cover, Charles Darwin, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

This is so useful! Thanks for going into this.

LikeLike