by Helen Currie Foster

When you read a passage and experience words that strikes home forcefully–so forcefully that you almost gasp–what did the writer do that moved you so?

I’m collecting examples. For my husband it’s John Steinbeck’s tide pool in Cannery Row:

“…When the tide goes out the little water world becomes quiet and lovely. The sea is very clear and the bottom becomes fantastic with hurrying, fighting, feeding, breeding animals…Starfish squat over mussels and limpets, attach their million little suckers and then slowly lift with incredible power until the prey is broken from the rock…”

I’ve never seen a Monterey tide pool. Yet Steinbeck made me feel I have. I want to sit at the edge of the tide pool, hear “the snapping shrimps with their trigger claws pop loudly” and see the “black eels poke their heads out of crevices and wait for prey.”

Why? Steinbeck’s description is so closely observed…it’s as if my own eyes and ears saw and heard.

What about food? Proust’s memory of a madeleine crumb dipped in his aunt’s tea didn’t initially resonate with me (a madeleine seemed too bland; I would’ve preferred a buttery, crunchy, tender croissant!)–until I read his analysis.

When Proust discovered that his second and third bites of the madeleine lacked the same impact–“the potion is losing its magic”–he stretched his mind further. He writes that the source of memory was not his sense of sight (though his description of the scalloped pastry is charming). Instead, his memory came from taste and smell: “But when from a long-distant past nothing subsists, after the people are dead, after the things are broken and scattered, still, alone, more fragile, but with more vitality, more unsubstantial, more persistent, more faithful, the smell and taste of things remain poised a long time, like souls, ready to remind us, waiting and hoping for their moment,…and bear unfaltering…the vast structure of recollection.”

No French bakery in my grandmother’s small Texas town, Itasca. But the memory of her kitchen still comes back when I smell lavender, or yeast–my grandfather’s lavender talc, my grandmother’s ineffably delicious yeast rolls.

Here’s another powerful example from The Orphan Keeper by Camron Wright, about a young man, kidnapped from his home in India, then sent to a dishonest orphanage which places him for adoption in America where he rejects any Indian heritage and suppresses all his memories that aren’t “American.”

As a student in England he’s taken to an Indian restaurant where–reluctantly–he smells, then tastes, what’s offered:

“The scent that swirled around his neck had started rubbing his shoulder, reminding him softly that once, a very long time ago, they had met….[He] took his first bite. The spices in his mouth grabbed hands and began dancing in rhythm across his tongue–cumin, garlic, peppers, ginger, tamarind, cinnamon, and more. They weren’t just dancing–they were cheering, clapping, celebrating, singing, reminiscing. They were pulling out wallets and showing each other pictures of their kids….The mingling spices, the familiar taste, it felt like a whisper arriving with the wind, more message than memory.”

Curry, of course. Just reading this made me long for mango chutney! And I thought it a powerful description, because closely observed, and particularly because until this moment we know the protagonist has been stubbornly resistant to anything Indian.

In A Gentleman in Moscow, by Amor Towles, do you recall the bouillabaisse scene? The three conspirators have carefully gathered the ingredients–hard to come by in Moscow; have picked up their spoons; and have taken their first taste. Count Rostov closes his eyes “to attend more closely to his impressions”:

“One first tastes the broth–that simmered distillation of fish bones, fennel, and tomatoes, with their hearty suggestions of Provence…One marvels at the boldness of the oranges arriving from Spain and the absinthe poured in the taverns. And all of these various impressions are somehow collected, composed, and brightened by the saffron–that essence of summer sun…[W]ith the very first teaspoonful one finds oneself transported to the port of Marseille–where the streets teem with sailors, thieves, and madonnas, with sunlight and summer, with languages and life.”

Bouillabaisse! Your memories may differ. Were you reading Julia Child and launching a kitchen experiment? Were you visiting Marseille, and were there still sailors, thieves and madonnas?

The Count has shared his memories, aroused by fish bones, fennel, tomatoes, shellfish and saffron. But your memories are your own. Also, the scene is powerful not just because it is closely observed, but also because it reminds the reader forcefully that at this point the Count has only his memories–he can’t leave the Moscow hotel, much less travel to Marseille.

I’m puzzled not to find food more “closely observed” in novels. A favorite moment: Virginia Woolf famously describes the boeuf en daube at the dinner party which is a central feature of the first half of To the Lighthouse. Mrs. Ramsay is thinking the cook “had spent three days over that dish,” as she prepares to serve it to her guests:

“…An exquisite scent of olives and oil and juice rose from the great brown dish as Marthe, with a little flourish, took the cover off. …[Mrs. Ramsay] peered into the dish, with its shiny walls and the confusion of savoury brown and yellow meats, and its bay leaves and wine, and thought, This will celebrate the occasion…”

Cookbooks, of course, intend to awaken our senses as we peruse the recipes. But the description of boeuf en daube in To the Lighthouse, with the mouthwatering anticipation it creates, has a different impact. It places us in the scene. It almost makes us, as readers, feel like guests sitting at Mrs. Ramsay’s table, alongside the odd characters Woolf has already introduced. Or possibly we also feel a bit like Mrs. Ramsay, the hostess, hoping to delight and reassure her houseguests, who are a difficult lot.

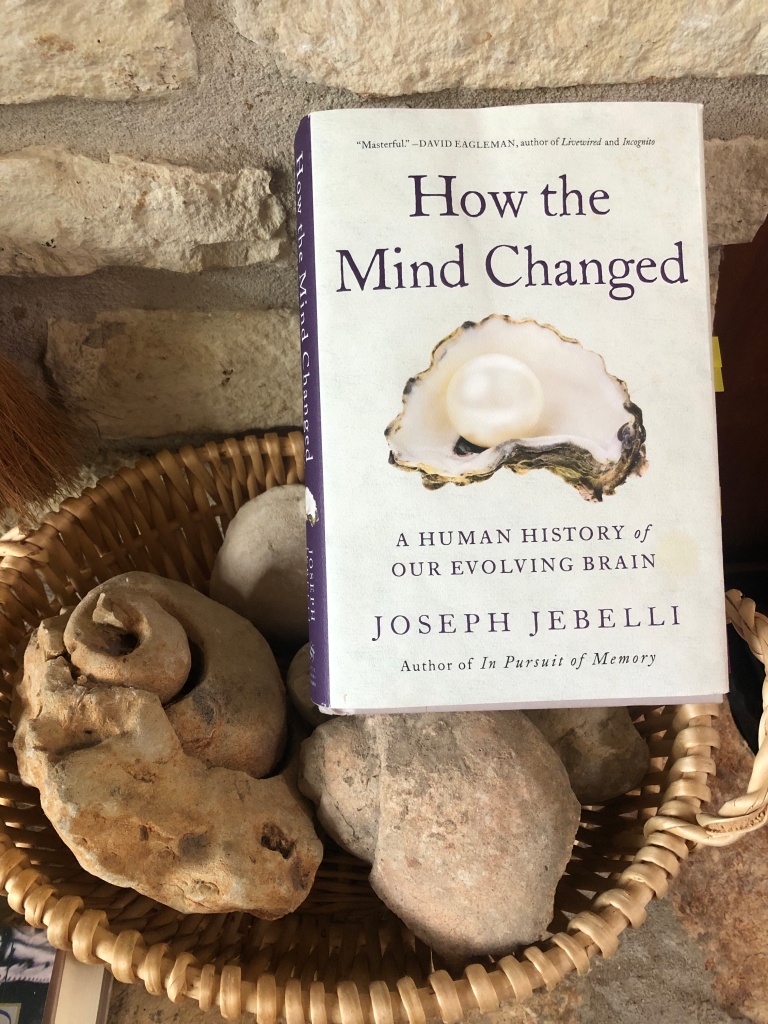

I’d love to hear other examples from readers. A “closely observed” passage can make us do just what the author wants: turn the page and keep reading! Right now I’m engrossed in Someone Always Nearby, Susan Wittig Albert’s fascinating novel about two real people, Georgia O’Keefe and Maria Chabot. I’m finding this a daring literary adventure about two daring and adventurous women, the artist you know and the woman who wanted to be indispensable to her.

It’s May–bluebonnets are gone, summer approaches. What tastes and smells bring back your summer memories? Grape popsicles, melting on the tongue? The clean bluegreen smell of Austin’s Barton Springs, mixing creek water and artesian spring water? The faint smell of chlorine from a pool crowded with splashing children? A mountain trail in the Rockies, with the cool green odor of aspen groves rising up from a creek? Dust blowing at the ball park, freshly mowed lawns, the faint rubbery smell of a sprinkler on a hot day? The smell of a roasting marshmallow just before it bursts into flame?

Good news from where I write: Ghost Bones, Book 9 in my Alice MacDonald Greer Mystery series set in the small town of Coffee Creek, Texas, will soon be out! With mystery, legal drama, and matters of the heart.

Helen Currie Foster lives and writes north of Dripping Springs, Texas, loosely supervised by three burros. She’s drawn to the compelling landscape and quirky characters of the Texas Hill Country. She’s also deeply curious about our human history and prehistory, and how, uninvited, the past keeps crashing the party. Ghost Daughter, Book 7 in The Alice MacDonald Greer Mystery series, was named Finalist in the 2022 Eric Hoffer Book Award Grand Prize Short List. Follow her:

https://www.helencurriefoster.com

and

https://facebook.com/helencurriefoster/

copyright 2024 Helen Currie Foster all rights reserved