by Helen Currie Foster

October 29, 2024

The mystery is solved! In my search for what I recalled as “the “Blitzkuchen” once served at Schwamkrug’s outside New Braunfels, in the Texas Hill Country, I had the name wrong. It’s a blitz torte, not a blitz kuchen! Several readers sent recipes from German cookbooks indicating that “Blitzkuchen” is a quick cake, usually one layer only. My memory, though? A tall two-layer confection, baked with meringue and almond flakes on top and between the layers! And in my memory, more meringue on the outside, plus some moistness in the filling.

Online I found Oma Gerhild’s “Oma’s Blitz Torte Recipe ––Lightning Cake.” https://www.quick-german-recipes.com/german-blitz-torte-recipe.html Each almond-flavored layer is baked with meringue and sliced almonds on top of the batter. The recipe offers either custard filling or whipped cream filling. I opted to finish off with whipped cream with powdered sugar and vanilla, not just inside, but around the cake (and in blobs all around the kitchen).

FINALLY! First, that lovely almond taste. Plus, everyone at the table now wore an attractive little white mustache of whipped cream. You don’t get that with a madeleine and a cup of tea, do you, M. Proust?

As October runs into November, Texas Hill Country towns are celebrating Oktoberfest, or, in New Braunfels, Wurstfest. Normally by now our trees would show some fall color––nothing like New England, of course. The cypresses by Lake Austin are turning bronze. Out here north of Dripping Springs, the possum haws are showing their red berries. The cedar elms turned bright yellow, then slowly lost their leaves. The live oaks, thankfully, stay green.

But this year? Drought brings bad news for trees. Cypress-lined creeks are dry…the cypresses’ arched roots groping into the earth for water. Downhill at our place Barton Creek is dry, and I mean dry, with only occasional small pools. Up on the limestone plateau the leaves on some smaller saplings just turned brown and fluttered to the ground, with the tree already looking dead. We’re watering, but in Stage 2 drought restrictions. Will our wells run dry? Have we drained the Trinity aquifers that lie hundreds of feet below?

So, to general geopolitical angst, I’ve added…tree worry.

Trees in books play such a role in our imaginations. After reading Johann David Wyss’s Swiss Family Robinson (1812)—where the shipwrecked family builds a tree-house on their desert island––I always wanted to live in a tree-house! https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Swiss_Family_Robinson We’re drawn to forests, home of the trees—scary, but sometimes the safest place. In The Sword in the Stone by T. H. White (1939), first of the four volumes that make up The Once and Future King, the Wart (the young Arthur, under Merlin’s tutelage) and Kay meet Little John who tells them about Robin Wood (explaining why it’s not “Robin Hood” and why he lives in the woods (or “‘oods”):

“They’m free pleaces, the ‘oods, and fine pleaces. Let thee sleep in ‘em, come summer, come winter, withouten brick nor thatch, and huntin’ ‘em for thy commons lest thee starve; and smell to ‘em with the good earth in the springtime; and number of ‘em as they brings forward their comely bright leaves, according to order…”

There the boys, the future King and Sir Kay, approach “the monarch of the forest. It was a lime tree as great as that which used to grow at Moor Park in Herefordshire, no less than one hundred feet in height and seventeen feet in girth, a yard above the ground….” Headquarters for Robin Wood and Maid Marian! And there begins a great and perilous adventure for Kay and Wart, who break into the castle of Morgan le Fay, Queen of Air and Darkness—to rescue prisoners paralyzed by magic. (Speaking of paralyzed victims of witches—note how C.S. Lewis later describes turned-to-stone courtyard figures in his first foray into fantasy, The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe (1950).)

One writer, Elisabeth Brewer, notes that “The Sword in the Stone shows a passion for trees that White shared with Tolkien. https://bit.ly/3Ceqk. How about the Ents we meet in Fangorn Forest, in J. R. R. Tolkien’s Middle-Earth? Trees that walk…and tend other trees. Not all trees are benign––including the wicked old willow which captures Frodo and friends (rescued by Tom Bombadil).

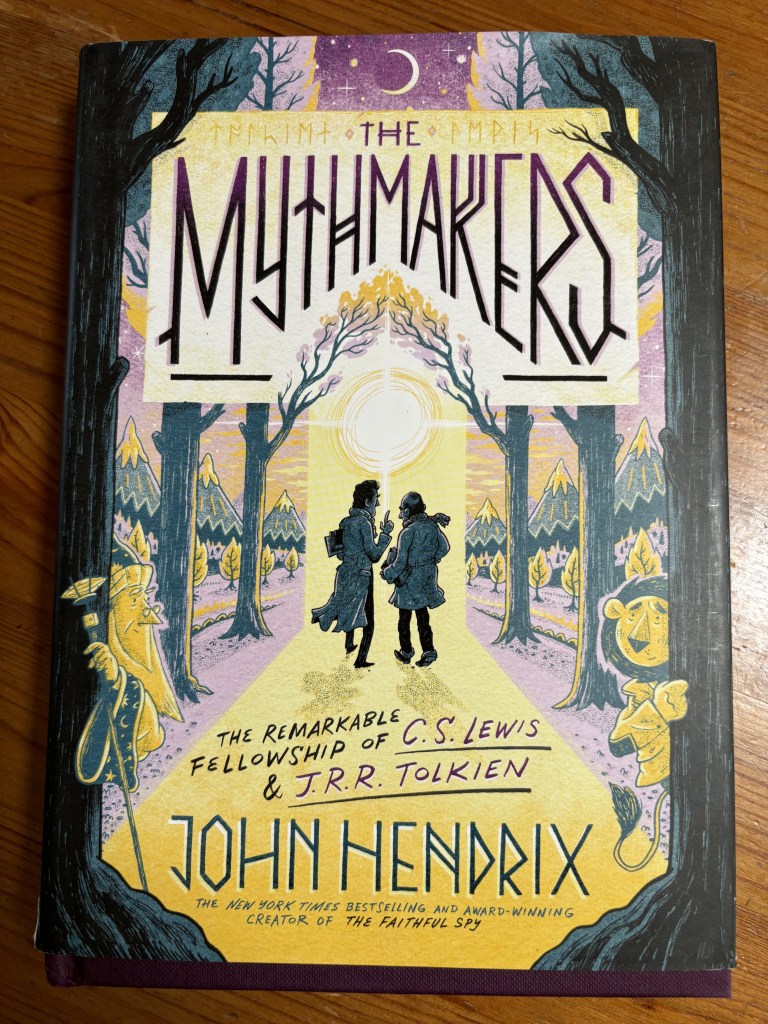

I’m reading a fascinating graphic (yes, graphic!) book about Tolkien and his close friend C.S. Lewis: The Mythmakers: The Remarkable Fellowship of C.S. Lewis and J.R.R. Tolkien, by John Hendrix. https://bit.ly/4hqiyFr

Tolkien and Lewis met in 1929 in Oxford, where they were, famously, members of a writers’ group, the Inklings, and shared many hours at The Eagle and Child. That’s not all they shared. In 1916, both men experienced horrific warfare on the Western Front in France. Young and just married, Tolkien fought in the trenches, then contracted life-threatening trench fever. At nineteen, Lewis was wounded by shrapnel (from friendly fire) on the Somme, and carried shrapnel in his body the rest of his life. Hendrix’s wonderful book uncovers the sort of salvation two disillusioned veterans found in the healing power of imagination, including Norse mythology and the European fairy tale. Tolkien knew of Yggdrasil, the sacred ash tree central to Norse mythology. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Yggdrasil; https://dc.swosu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2130&context=mythlore

And how the worlds created by Lewis and Tolkien fired our imaginations! The fantasy world of C.S. Lewis’s Narnia emerged when The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe was published (1950). Tolkien’s The Hobbit, or There and Back Again, was first published in 1937 but became a pop-culture phenomenon only in 1960’s, when the paperback edition became available. https://time.com/4941811/hobbit-anniversary-1937-reviews/

Both Lewis and Tolkien had copies of The Sword in the Stone early on. Indeed, in 1939 it was a Book-of-the-Month Club selection. T. H. White 1964 obituary, https://nyti.ms/4hlasht. Curiously, Hendrix’s book on Tolkien and Lewis doesn’t mention T. H. White, perhaps because Hendrix focuses on the impact of war; T.H. White 1906-1964) was born too late to serve in World War I. Nor was he an Oxonian. While C.S. Lewis reportedly disparaged The Sword in the Stone in 1940, he later invited T. H. White to the Inklings if he ever visited Oxford. https://bit.ly/4f4wcww (“Dickieson post”). Perhaps Hendrix doesn’t mention T. H. White because unlike Tolkien and Lewis, though he creates a fantasy world, White grounds The Once and Future King firmly in England.

But Elisabeth Brewer commented in T.H. White’s The Once and Future King that The Sword in the Stone shows a passion for trees that White shared with Tolkien. (Dickieson post.)

What about powerful trees in more recent books? Consider the Whomping Willow, in J. K. Rowling’s Harry Potter and the Wizard of Azkaban? https://bit.ly/4f1koex Magic—but terrorizing—it reveals the secret passage which ultimately allows Harry and friends to discover––well, remember? Indeed, Harry reminds us of T. H. White’s Wart, both with an earnest determination to do right, and a magical tutor.

Maybe children are especially open to tree power because they still climb trees. My dad swooped us off to grad school in Atlanta, and then to Charlotte, before we moved back to Texas. In the southeast I discovered the power of pine trees. We children built an admirable and secret treehouse in the woods, where we surveyed the world from on high. No parents came near to scold or warn: deep in the trees we ruled our own domain. Later in Carolina at eleven, I could climb the neighbors’ big back yard pine all the way to the top. The tree swayed slowly back and forth, but I could see the entire neighborhood and beyond. Tree power.

Out here on the Edwards Plateau, in the rugged karst landscape above a hill country creek, live oaks rule. The big evergreens, up to sixty feet tall, with a wide crown and massive limbs close to the ground, are Quercus Virginiana. They often grow in a circle—and you know they are communicating through their root systems. https://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2021/05/04/993430007/trees-talk-to-each-other-mother-tree-ecologist-hears-lessons-for-people-too

The way live oaks vary their leaves makes identification tough. On the Edwards Plateau, the species passes into the “shrubby Texas Live Oak”—shorter with smaller trunks: “…[I]ntermediate forms occur between the variety and the species and the distinctions are often difficult,” per Robert Vines, Trees, Shrubs and Woody Vines of the Southwest (1960). Well, thanks.

Now, in drought, with grass turned grayish tan, with dirt powder-dry beneath our feet, we treasure the blessed green of live oaks, often home to swings and hammocks, and providing wide shade to houses, pastures, and somnolent cattle.

Trees inspire us. We know Shakespeare’s song: “Under the greenwood tree, who loves to lie with me…” (As You Like It). The first poem in Wendell Berry’s A Timbered Choir begins, “I go among trees and sit still.”

Mary Oliver’s “Honey Locust” begins,

“Who can tell how lovely in June is the

honey locust tree, or why

A tree should be so sweet and live

in this world?”

Robert Frost knows his trees: The Road Not Taken, Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening, Tree at My Window, Spring Pools, so many. Of course, his Birches:

“When I see birches bend to left and right

Across the lines of straighter darker trees,

I like to think some boy’s been swinging them…”

Frost makes it easy to imagine “some boy” swinging the birches—or Frost imagining that, as he marched through a yellow wood.

And then e.e. cummings, My Father Moved Through Dooms of Love—I like this verse:

“My father moved through theys of we,

Singing each new leaf out of each tree

(and every child was sure that spring

Danced when she heard my father sing)”

And Gerard Manley Hopkins, Spring and Fall:

“Margaret, are you grieving

Over Goldengrove unleaving?”

Yes, trees: later in the poem we find when “worlds of wanwood leafmeal lie.”

The forecast calls for rain. Please cross your fingers.

Helen Currie Foster lives and writes the Alice MacDonald Greer Mystery Series north of Dripping Springs, Texas, loosely supervised by three burros. She’s drawn to the compelling landscape and quirky characters of the Texas Hill Country. She’s also deeply curious about our human history and how, uninvited, the past keeps crashing the party. Currently she’s working on Book 10. Her protagonist, Alice, gets into legal drama, and matters of the heart. And yes, Alice does have a treehouse.

Halloween is near, so I shall tell a scary tale, one about a wicked witch and innocent little children.

Halloween is near, so I shall tell a scary tale, one about a wicked witch and innocent little children. Library school was—not adorable. It was challenging. Some courses were nerve-wracking. When they said library science, they meant science. In the words of the Library of Congress cataloger teaching the Organization of Materials course, as she looked out over a sea of bewildered students— “Come on, people. Cataloging isn’t rocket science. Rocket scientists couldn’t handle it.”*

Library school was—not adorable. It was challenging. Some courses were nerve-wracking. When they said library science, they meant science. In the words of the Library of Congress cataloger teaching the Organization of Materials course, as she looked out over a sea of bewildered students— “Come on, people. Cataloging isn’t rocket science. Rocket scientists couldn’t handle it.”* While I read, Cuthbert sat on the floor beside my chair and stroked my panty-hose-clad shin. Small children find panty-hose fascinating.

While I read, Cuthbert sat on the floor beside my chair and stroked my panty-hose-clad shin. Small children find panty-hose fascinating.

In Chapter 1, Dr. Blair Cassidy, professor of English, arrives home one dark and stormy night, walks onto her front porch, and trips over the body of her boss, Dr. Justin Capaldi. She locks herself in her car and calls the sheriff. The sheriff arrives and . . .

In Chapter 1, Dr. Blair Cassidy, professor of English, arrives home one dark and stormy night, walks onto her front porch, and trips over the body of her boss, Dr. Justin Capaldi. She locks herself in her car and calls the sheriff. The sheriff arrives and . . . poisons. As a pharmacy technician during World War I, she did most of her research on the job before she became a novelist. Later she dispatched victims with arsenic, strychnine, cyanide, digitalis, belladonna, morphine, phosphorus, veronal (sleeping pills), hemlock, and ricin (never before used in a murder mystery). In The Pale Horse, she used the less commonly known

poisons. As a pharmacy technician during World War I, she did most of her research on the job before she became a novelist. Later she dispatched victims with arsenic, strychnine, cyanide, digitalis, belladonna, morphine, phosphorus, veronal (sleeping pills), hemlock, and ricin (never before used in a murder mystery). In The Pale Horse, she used the less commonly known  Aforethought.

Aforethought. for accuracy. Colleague

for accuracy. Colleague  writing. But she confessed in a magazine article that

writing. But she confessed in a magazine article that