by Helen Currie Foster

You go to a play, you’re reading the program, you’re waiting for the curtain to go up. It does. And onstage a character comes alive. You not only believe in that character—suddenly you feel that character is real.

After the play, in the lobby, out comes a chattering group of actors, one of whom is—the character you believed in! But it’s merely…another human being!

This happens to me over and over at Austin Shakespeare productions. I remember sitting riveted, watching Othello preparing to smother Desdemona, his face just a few feet from the front row of the Rollins Theatre. “No, no!” I wanted to scream. Minutes later, still quaking from the death scene, I watched the actors come back out for their traditional after-talk with the audience. I watched brokenhearted Othello plop down in a folding chair and grin at us––morphed from Othello into actor Mark Pouhé. At Free Shakespeare outdoors in Austin’s Zilker Park I held my breath, watching young Romeo climb the balcony to talk with Juliet, enchanted––like Juliet––by every word he uttered. Then at intermission, still in costume, actors came out and climbed the hillside, shaking buckets for donations, including…Romeo! Jarring to think he’d time-traveled from sixteenth century Verona to an Austin hillside. https://www.austinshakespeare.org/

You may be thinking, “I know all about that––it’s just the ‘willing suspension of disbelief.’ Coleridge, right? Maybe you’ve just got an aggravated case!”

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Samuel_Taylor_Coleridge

But the question is—how exactly can actors do that? Maybe because Shakespeare has made Othello and Romeo so active, so appealing, so fascinating, so human, so alive in their loves and hates, that we believe in them, and we must hear their story. Others call such fixations our willing contract with actors, in exchange for being entertained––so long as the illusion is not spoiled. See The Actor’s Edge Online, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zdGM7QzFJhM

As always, Shakespeare says it best. In the Prologue to Henry V, his Chorus begs the audience to use their own imaginations to make the small wooden stage come alive with the war between the “two mighty monarchies,” England and France:

“Think, when we talk of horses, that you see them/

Printing their proud hoofs I’ th’ receiving earth./

For ‘tis your thoughts that now must deck our kings,/

Carry them here and there, jumping o’er times,

Turning the accomplishment of many years/

Into an hour-glass…” Henry V, Prologue.

That’s genius.

Coleridge himself recalled his agreement with Wordsworth as follows: that while Wordsworth would write poems about the charm of everyday things,

“It was agreed, that my endeavours should be directed to persons and characters supernatural, or at least romantic, yet so as to transfer from our inward nature a human interest and a semblance of truth sufficient to procure for these shadows of imagination that willing suspension of disbelief for the moment, which constitutes poetic faith.” (Emphasis added.)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Suspension_of_disbelief [Also spoken of as “the concept that to become emotionally involved in a narrative, audiences must react as if the characters are real…”] https://www.oxfordreference.com/display/10.1093/acref/9780199568758.001.0001/acref-9780199568758-e-267

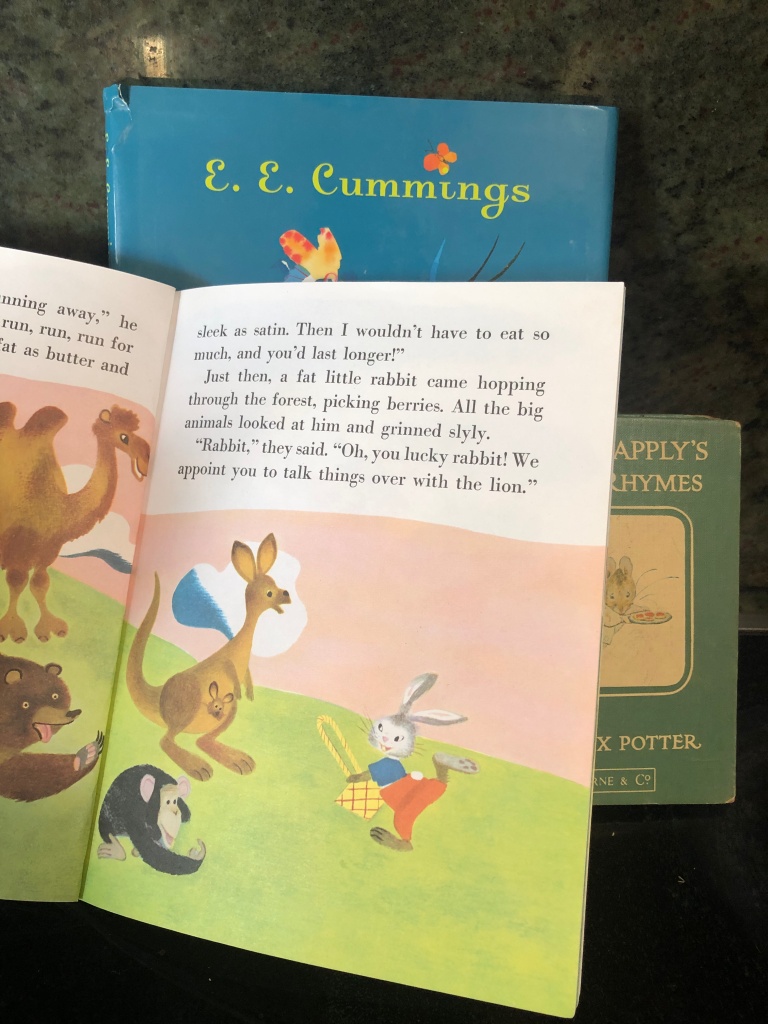

By buying a theatre ticket, or a movie ticket, we’re inviting an agreement like the one between the child who begs, “Tell me a story!” and the adult who responds, “Once upon a time…” In those two phrases, the contract is made. The child agrees—likely longs––to suspend disbelief, and the storyteller promises a world where the unexpected (even the unbelievable) can happen. Talking animals…bears with beds and chairs…

You and I happily suspend our disbelief when the characters become real to us, even though the events may be beyond “belief.” Harry Potter! Indiana Jones and the Dial of Destiny! Lord of the Rings! Star Wars!

What does this have to do with mysteries? At least the protagonist in any mystery must come alive for us. If you’re a Louise Penny fan, you appreciate how Gamache smiles at his wife, how he strokes his dog. As for Donna Leon’s Inspector Brunetti, I know him well; I’ve followed him upstairs to his Venetian apartment so many times, practically huffing with him on that last staircase. I’ve watched him choose a panini to have with coffee in his favorite coffee bar—indeed, I can practically smell the espresso. I’ve stood with him in the police boat as it bounces across the lagoon to a murder scene. He’s become so familiar, so…well, real to me. V.I. Warshawski in the Sara Paretzky novels? I know the emotion she feels when she touches her mother’s cherished wine glasses, I feel my blood pressure rise with hers over injustice. And Robert Galbraith’s team, Robin and Cormoran? I ache with the pain of Cormoran Strike’s prosthetic as he runs, trying to catch a suspect; I feel Robin’s fear as she opens a door to a dark hallway. I peer over Joyce’s shoulder as she writes in her journal in Richard Osman’s The Thursday Murder Club series.

A story (play, movie, mystery novel) demands a setting in which the protagonist comes alive for us. We’ve suspended disbelief when our favorite mystery characters no longer exist merely as ink on a page, as lines in a Kindle. Coleridge’s goal was to create “a human interest and a semblance of truth sufficient to procure for these shadows of imagination that willing suspension of disbelief for the moment.” We’re interested in what happens—a “semblance of truth”––to a character who arouses our “human interest.” The author, actor, director, has made us feel in league with our favorite characters. We’ve become collaborators with them, sharing their adventures, their frustrations, their fears. Suspending disbelief may be why we’re so anxious when our protagonists face danger, why we’re indignant when they’re treated badly, why we’re so relieved when they’re vindicated.

Of course a mystery plot may challenge imagination. The perfectly timed rescues in Daniel Silva’s spy thrillers…and the magnificent art restoration skills of his hero, Gabriel? The exquisitely choreographed capture and totally successful interrogation of Grigoriev in John Le Carré’s Smiley’s People?

Or the clever solutions deftly reached by ex(?)-spy Elizabeth and her friend Joyce at a foreign agent’s swimming pool suspended high above London, in The Bullet that Missed? https://amzn.to/45NxJlE

Knowing how reality usually works, we worry how plans go awry, how colleagues disappoint, how villains can foil. We shake our heads, fearfully anticipating that the plan will fail, and our character’s bluff will be called. But we’re still hoping, and holding our breath every second. And we keep turning the page.